The past few years have been full of stories of beloved childhood shows and animations being canceled or removed without a home anywhere to be seen in the streaming world. With the continuity of the streaming wars and mergers such as Max, animation is often the first to be dealt the lethal blow for the sake of profit.

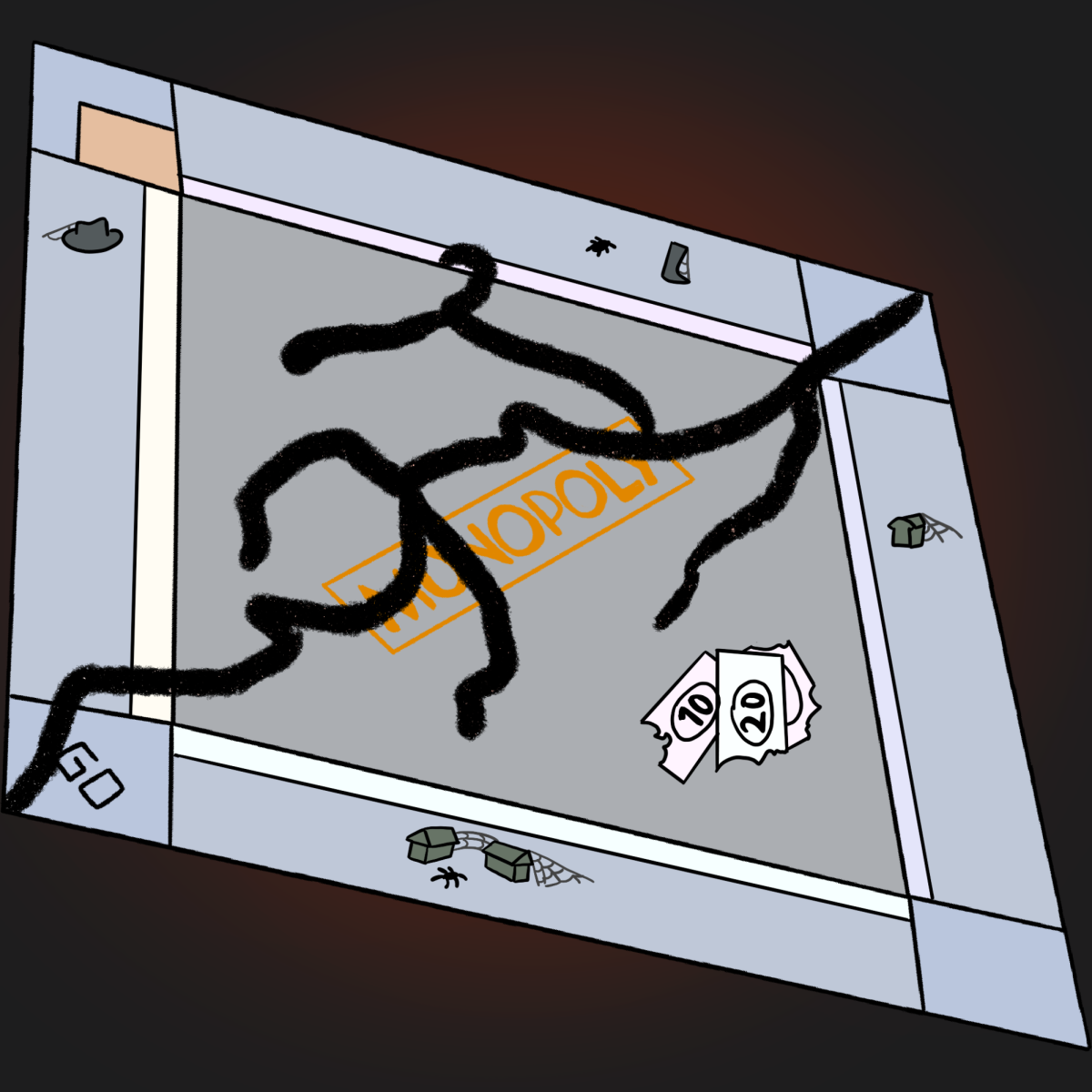

The merger between HBO Max and Discovery Plus dealt one of the most devastating blows to animation as Warner Brothers announced that they would be cutting up to 40 animated shows from the service. This would leave multiple shows, such as “Infinity Train” and “Close Enough,” without a place to watch them other than just buying them. Especially with the case of “Infinity Train,” created by Owen Dennis, with the show being canceled and taken off of Max with no communication to the team, leaving them without jobs in a competitive market.

Dennis would say on his blog later: “I think the way that Discovery went about this is incredibly unprofessional, rude, and just straight up slimy. I think most everyone who makes anything feels this way.”

There is also the problem of the fight between unions and studios. As of Nov. 25, of this year, unions were able to broker a deal with studios that gives animators more protections, though its ratification still needs to be voted upon. This includes mandates for consultations and notifications to animators for the use of AI as well as a 14.5% wage increase over a three-year period while also supporting workers’ right to remote work. The animation guild, TAG, has also started to expand its reach outside of LA County and potentially outside of the U.S.

However, while this is good news to animators for protection during working cycles and those in entry-level positions, it doesn’t address the issue that animation is usually the first to be cut in the vast majority of cases. Netflix is infamous for this. During a large drop in subscribers in the first quarter of 2022, they would proceed to cancel already going shows and even some that were still in production. One of the most egregious examples is Netflix’s “Inside Job.” Months after its renewal, the streaming service announced that they would be scrapping the show under issues with “metrics and cost-cutting,” a generally unprecedented move

“Over the years, these characters have become real people to me, and I am devastated not to be able to watch them grow up.” Said Shion Takeuchi, the show’s showrunner and creator.

This phenomenon has only become more and more common with the power that streaming services afford to studios, allowing them to squish certain shows before they have the chance to fully form. Large volumes of cancellations are no longer about viewership or rating at this point; instead, they are ways to save studios money in the long term. Cutting shows completely off of certain websites means that those studios don’t need to pay residuals to the people who work on the shows, especially before large upticks in viewership. Last year, Max cut “Over The Garden Wall” just weeks before the start of the fall season, when it had the largest number of viewers. The merger that Discovery and HBO did just last year left them in almost 40 billion dollars of debt, leaving them desperate to find cuts anywhere they could, which ended up being animation.

All of this creates an environment where if a show doesn’t hit the quota for being marketable or instantly profitable, that show is very likely to be dropped, no matter the creative or critical position that the show is in. The best example of this is Bob-Waksberg’s “Bojack Horseman,” which ran for six seasons, with its seventh being canceled by Netflix. Even with mass critical and audience acclaim, the ending of “Bojack Horseman” was a premature one. With Netflix adopting a new business strategy of pushing for paid watching with ads, the streaming service has become more dependent on getting hit shows to attract advertisers and fast subscribers rather than fostering a network of quality shows.