Is gay an analogy for straight? That’s the question that the LGBT community has struggled to answer since its formation, more so than ever in the past decade. Yes: gay people are equivalent to straight people in nearly every manner; therefore, gay attraction is nothing more than a permutation of sexes. Or No: the “queerness” championed by the LGBT extends beyond sex, into social conventions.

Although the former answer is still the most widely accepted, I’ve seen a push towards “queer culture” in recent years. It’s a perfectly logical conclusion, in one regard: the LGBT has always been about creating a place for outcasts, who naturally come in more forms than lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender. The “permutation” explanation, therefore, is an oversimplification. In condoning love between two women, do we assume that they’ll be typical in every other regard – that they’ll present with femininity, respect the institution of marriage and settle down quietly?

This notion is fiercely rejected. For example, asexuality, now associated with garlic bread and corvid species – among other things – has become an idea far greater than the lack of sexual attraction. An asexual person does not equal a straight person minus sexual interest; inherently, they claim, they’re more practical, more in touch with nature, more keen on cuisine and more engaged with intellectual pursuits. By now, each sect of the LGBT has adopted a distinct culture; flags, symbols and tokens are all but necessary in cementing a sexual identity. But this form of tribalization has disturbing consequences.

The clublike nature of sexuality-based communities, for one, seems almost commercialized – advertising an aesthetic or brand. In choosing a label by which to identify, you’re also choosing a set of activities and a designated appearance. It’s particularly attractive to adolescents, who seek kinship while navigating their confusing feelings. Likewise, heterosexuality is made dull in comparison. Many an LGBT youth has said, I’m so glad I’m not straight! Why? Because straightness is boring.

Lesbian-ness, which has adopted increasingly nuanced definitions throughout the ages, is currently accepted as “queer attraction to women” – and includes every abstract variety of womanhood and femininity. But how is queer attraction differentiated from straight attraction? It’s not quite clear. The lesbian community is more connected to alternative fashion than it is to same-sex relationships.

And while many find comfort in a clearly defined sexual culture, to others it’s alienating. Suppose you love a girl, but haven’t watched Adventure Time, don’t play Stardew Valley, won’t cut your hair short and never really got into theater. Are you a true lesbian? Do you deserve to call yourself one? Moreover – will anyone understand the way you feel?

The inclusion promised by the LGBT has become exclusiveness; labels belong only to those who have met their cultural criteria. And the specificity of sexuality – queerness found in what people we love, the way we love, the degree to which we love, how many kinds of love we can have, whether their gender conventions come into it, whether ours do – has confined straightness, normalcy, to a set of strict social expectations.

Love is love! I’ve heard the phrase many times. Is it? Or is it a list of categories, thoroughly researched, finely dissected, sliced along the lines of every fluctuation of heart? When we ascribe rigid definitions to our ambiguous feelings, how much allowance are we truly giving ourselves?

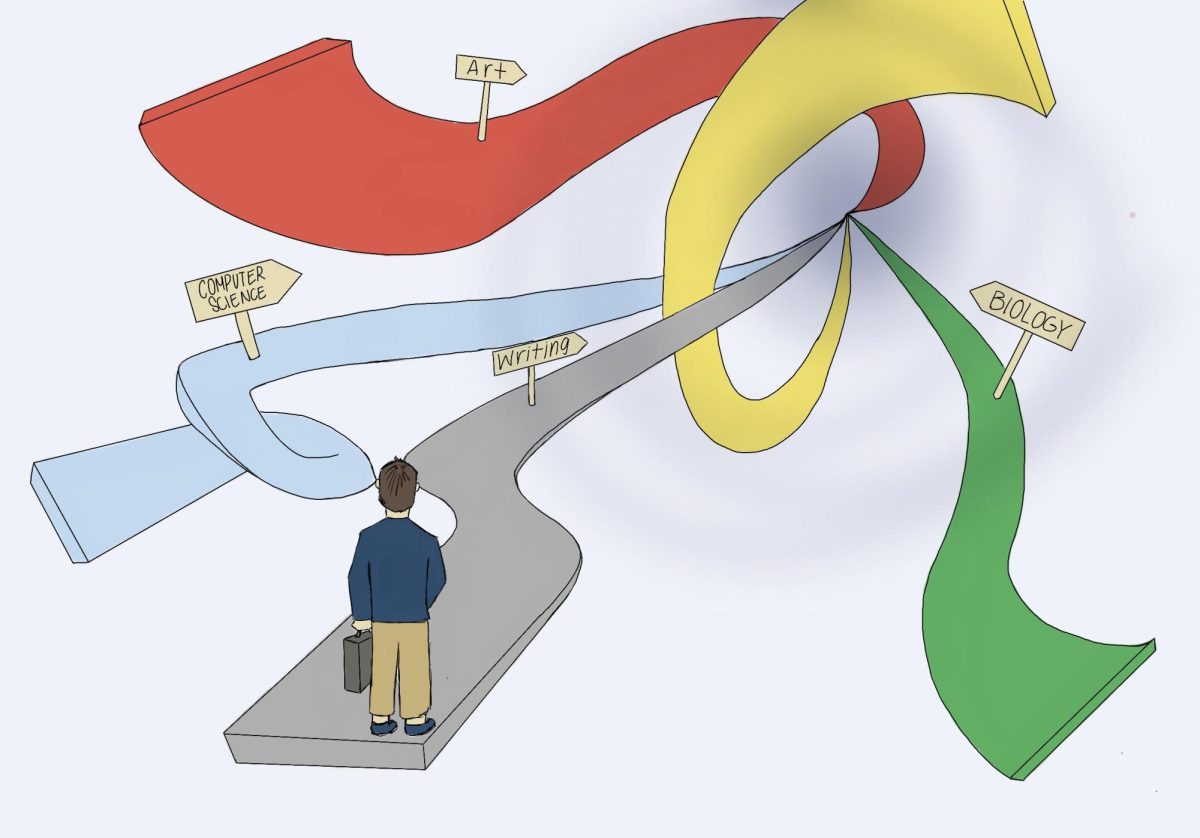

Now – rather than determining whether we’re “female-attracted”, “equally female-attracted and male-attracted”, “primarily female-attracted and partially male-attracted”, etc. – myself and thousands of others have opted to join the unlabeled movement, concerned with sexuality insofar as it presents itself with “yes or no” questions. We “swing both ways”, or we’re “for the boys”; at any rate, detached from who we are, and focused on what we do. Is gay an analogy for straight? Why call yourself gay or straight? Is it necessary for love?

Perhaps sexual identity is a guiding truth for some, but the rest of us may always be subject to contradictory sentiments, not acting in accordance with a singular word or well-established community. Our world isn’t dominated by people with uncomplicated, textbook-definition emotions. Complexity isn’t queer; it’s common! The normalcy we’ve come to revile, therefore, must expand to fit this range of human behavior.

To me, at least, being normal doesn’t mean representing an average, or believing in the status quo. Instead, it’s about the freedom to make decisions without respect to my demographics – the freedom to be without being queer.