Indie game “Undertale” showcases the best of the Underground (Josh Santiago)

February 12, 2016

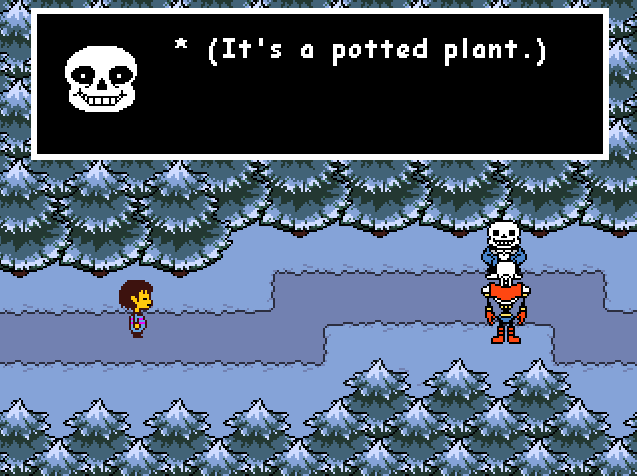

On Sept. 15, Toby Fox released “Undertale,” a charming indie game with nostalgic visuals and unconventional storytelling that has captured the hearts of the internet.

On the surface, “Undertale” sells itself as an innocent, typical role playing game, drawing influence from games like “Earthbound” or even “Pokemon”. The characters are charming and the premise is simple enough: in every battle, you can choose to befriend and spare each enemy, theoretically being able to beat the entire game without a killing a single enemy.

Rather than disconnected choices or cutscenes, most of “Undertale’s” choices come from direct actions from the player. Exploring the dialogue options to spare enemies transforms the game into a visual novel esque battle, where the right “choices” come from evaluating enemies as people and accommodating for their needs. Each encounter is fresh, assuming you make an attempt to spare every enemy. This is in direct contrast to the combat option, which stays stagnant and repetitive. This is the game’s attempt to hold the player accountable for every character death. Every character matters, even the first “Froggit” at the beginning of the game. By the end of the game, the characters and the very fate of the “Undertale” universe lays within the player’s hands, where the ending depends on which characters were killed or spared.

“Undertale” has been known for its witty writing and impactful story. Its humor is successful for what it is trying to accomplish. Every line of dialogue has the potential to be the internet’s next meme. The creator clearly knew what audience and demographic to pander toward after working on viral webcomic “Homestuck,” as the story hits very similar notes as dark tones masked by whimsical visuals mixed with somber implications. Finding out what every character is fighting for adds to their individual charm, as well as incentive to play through as a pacifist. Regardless of whether enemies seek money for bakeries or escape from a soulless existence, each character feels real and organic. Befriending enemies makes players feel like they truly gained their friendship, as optional commentary from specific characters are peppered throughout the game as a reward for keeping them alive. Even characters initially deemed flat, such as Sans or Alphys, eventually reveal their sheer depth in motivation as the game progresses.

This critique on RPG values is where “Undertale” shines. The game can almost be described as postmodern, rewarding those who seek new angles for conventional puzzles and problems, yet punishing those who stay within old habits. In game, modern RPG activities such as “level-grinding” and “farming” are not only repetitive but inherently inhumane, if only because of the implications they hold. The slaughter of in-game enemies for the sake of “leveling up” seems reasonable in context, but in a “real-world” point of view, it’s horrific and unnatural.

“Undertale” implicitly discourages these actions, deconstructing them in order to expose the mindset as problematic. The opening tutorial instructs players to “strike up a friendly conversation” with enemies, rather than engage in combat. But though the “correct option” is to settle the battle without violence, the choice to fight is ever-present, ready to account for impatient players who just want the battle to end. The only immediate consequence for forceful victory is that the action directly forces players to give into the main antagonist’s mindset of “Kill or be killed.” Giving into the mindset strays the player further away from the true ending, and mercilessly plowing through the game introduces players to horrid responses from the game’s characters.

The dark and eerily subtle changes that occur when the player chooses to go through with a traditional RPG mindset are powerful and haunting. Choosing to not only fight and kill, but actively hunting down enemies for EXP, sends the player down a dark spiral. The fan-proclaimed “genocide route” constantly punishes those who treat “Undertale” with a traditional video game mindset. The bosses get harder, the music gets slower and more demented and the dialogue loses its heart and humor as every character fears for their life. A “Genocide route” is inherently worse as a standalone game, with good reason. In any other circumstance outside of context, a typical RPG protagonist is terrifying, as enemies lay helpless against its ever-expanding power. “Undertale” personifies this, with certain circumstances permanently altering aspects of the game. What is most terrifying is that getting to the “genocide” ending is purely a choice by the player, as it is impossible to come across by accident.

But what is truly interesting is the following and fanbase “Undertale” garnered. For 15 straight weeks, “Undertale” ranked number one for amount of fan activity on Tumblr. Support for “Undertale” pushed the game to win GameFAQ’s “Best. Game. Ever.” poll, beating out “Pokemon” and “Super Mario 64”. “Undertale’s” online presence is more than substantial, much to the annoyance of those who disliked or do not associate with the game. Colloquialisms such as “memetale” or “underfail” have arisen to critique the game’s abundant presence and overhype of its content. Its overexposure is unfortunately more than detrimental, as the game’s offbeat humor and experience as a game is almost universally considered best when left unspoiled. Key events, such as the ending reveals of pacifist runs have been accepted into modern “Undertale” fandom but the power and meaning of the scenes are ruined if prior knowledge seeps into the minds of new players.

However, when kept unspoiled, “Undertale” is a truly unique experience. Fans see the game as “influential and life-changing,” as its innovation of storytelling and meta-concepts make the player a part of the universe. Under the circumstances, “Undertale” had the potential to fizz out as just another indie game funded by Kickstarter. Its fans could have lost interest, and critics could have panned the game. Or even worse, “Undertale” could have been overlooked all together.

But it refused.