Selling Point: Stop marketing films as “diverse” (even if they are)

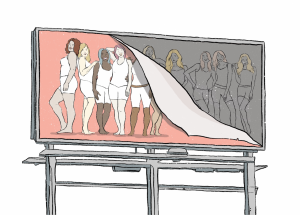

Movies showcasing diverse characters market their films in ways that tokenize minority populations, often harming their box office success.

November 11, 2022

Dear reader,

Christmas decorations. “The Office” episodes. Pasta. These are all things that are ruined when overdone.

Something I’ve recently added to this internal list of mine is the way that films push their “diverse representation” angle way too far. More and more, I’ve noticed that movies considered “groundbreaking” for their inclusion of minority groups have been doomed to fail, even before release.

A press release for the movie “Bros,” released in September, called it “one of the first romantic comedies from a major studio to feature an almost entirely 2SLGBTQIA+ cast.” There is no denying that this is a great step forward, but it’s a poorly focused marketing tactic.

“Bros” grossed only half of the 9 million that its “major studio” predicted for its opening weekend. The film lost out on millions of viewers, making it an unfortunate missed opportunity to highlight a rare film with lighthearted LGBTQ+ representation that was actually made by queer creatives.

“Aggressively marketing a movie as a glass-ceiling breaker can make it feel like homework for viewers,” Variety argued. “Universal leaned too much into the film’s importance instead of marketing [it as]…a comedy that’s, well, actually very funny.”

This isn’t just a blockade in the path toward equal representation—it’s a step back. Reminding audiences of how “diverse” your movie is only reemphasizes the constant othering of various populations. Using minority representation as a selling point reduces identity to something that can be marketed and packaged for consumption, an inherent tokenization of historically oppressed people.

These marketing techniques originated in the very first Hollywood films with non-white actors, who were often given stereotypical and demeaning roles. At the time, though, using diversity as an advertising angle wasn’t to satisfy public criticism or display some sort of “wokeness.” Instead, their selling points focused on the exotic, and almost fantastical features of these non-white actors. Though the intent was different, the effect was the same.

This tokenization, however, is in no way limited to race or sexuality. Musician Sia’s 2021 sh*tshow “Music” (I have no better word to describe this movie) focused on a woman named Zu’s struggles in raising her sister named Music, who was described in an official synopsis as “a teenager on the autism spectrum whose whole world order has been beautifully crafted by her late grandmother.” It’s ironic that this describes Music’s existence as being crafted by someone else, because one of the most harmful long-standing stereotypes of autistic people is that they cannot have autonomy or individuality.

The few scenes from Music’s “perspective” were sensory overload-inducing musical sequences promoting Sia’s original songs. Otherwise, she was merely a flat character (played by an allistic actress, no less) supporting Zu’s redemption arc, once again contributing to the dehumanization of autistic and disabled communities.

Furthermore, the commodification of diversity causes viewership to become segregated across ethnic lines by design—but change is possible. A 2017 study by communications researchers from the University of Michigan and the University of Pennsylvania found that movies advertised toward Black audiences could succeed when marketed toward a broader clientele.

The study, fronted by Morgan Ellithorpe, an assistant professor of communications, categorized a number of popular films as either “Black-oriented” or “mainstream” based on the plot and racial makeup of the cast. Around 2000 Black and white adolescents were asked to sort the films into the two groups and mark whether they’d seen them.

The results were surprising. In one example, 48% of Black respondents had seen the “12 Years a Slave,” and overwhelmingly categorized it as a “Black-oriented” film. On the other hand, only 23% of white respondents had seen the movie, yet still perceived it to be almost 20% more “mainstream” than the Black respondents did, meaning that they believed they were within the movie’s target audience.

According to Ellithorpe, part of this is because marketing campaigns often preemptively gauge their audiences and then try to reach those isolated groups of viewers, rather than the general population.

“[Black-oriented films] are advertised in previews of other Black-oriented films, so it becomes a cycle where audiences who aren’t seeing those films aren’t being exposed to the previews and [therefore], won’t see the films,” Ellithorpe explained.

Her team believes their findings can convince marketing teams to successfully advertise their movies to broader audiences. If white moviegoers believe films focusing on Black stories are mainstream, then Hollywood will be more inclined to produce diverse media.

With this logic, the reverse can also be true; there can (and most definitely will) still be films with only white actors, which isn’t an issue. However, as with “Black-oriented” content, these films should also be appealing to POC audiences (read: not racist).

Thankfully, the effort to redesign marketing campaigns for diverse films is already underway. Both major studios and independent films have found success in marketing their movies to wider audiences.

“Everything Everywhere All at Once” embodies this success. Released in March, it grossed $100M against its $14M budget, became the highest-rated movie on Letterboxd and skyrocketed up numerous publications’ Best of the Year lists.

As an indie film with a major subplot concerning a Chinese mother’s struggle to accept her queer daughter, “Everything Everywhere” seemed too niche to garner mainstream interest. But due to its wide-reaching campaign advertising its action-packed scenes and unique multiverse storyline, it broke the mold.

“[‘Everything Everywhere’] is about Asian American characters without being marketed as an Asian American film — its characters simply are, and just as relatable in all their cultural and personal specifics as anyone else,” film critic Alison Willmore, who herself is Asian American, stated for GQ.

Four of those words sum up my argument perfectly: “Its characters simply are.” Not overdone, and not played like a broken record. Ironically, it’s starting to look more and more like the secret to successful diverse media is not to market it as diverse at all. Of course, the intersectional issues of racism, homophobia, and ableism in film are far more complex. But if something as corrigible as a misguided press release can amend the harms of tokenization, and a single moviegoer outside of a film’s marketed audience can expand its reach, then change just might be easier than we think.

Until next month,

Lauren Chen