Languages are more than words: the sound of crumbling roots

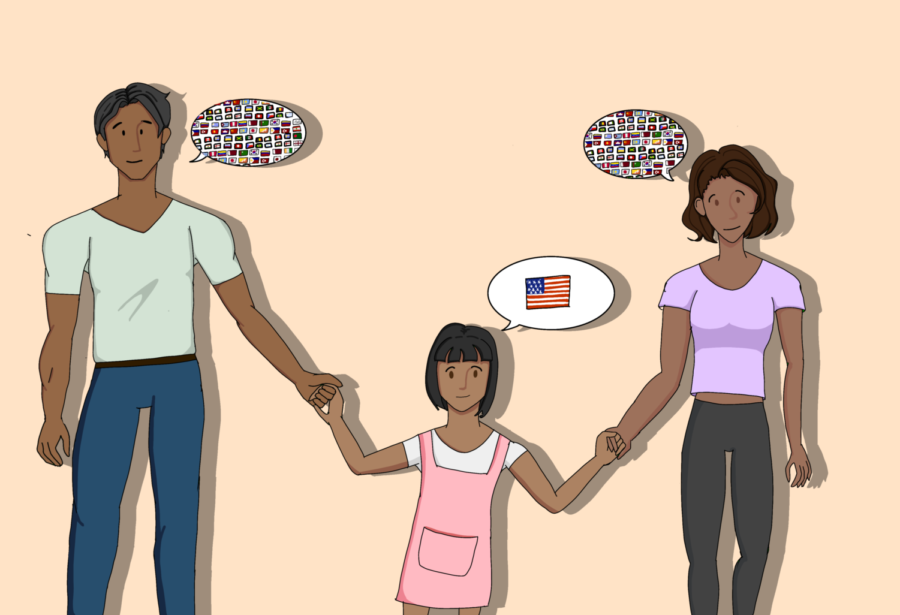

Many children of immigrants in America are losing their fluency in their native language. This process is described as “language attrition”.

June 8, 2022

As of 2022, only five countries do not claim an official language, and we are living in one of them. With up to 430 languages spoken, the U.S. is known to be among the most linguistically diverse countries.

However, this rich variety of languages is in danger. As people immigrate to America and assimilate to a new society, they often leave a rich culture behind along with the foreign language that connects them to it.

According to the 2018 American Community Survey, around 21.5% of people speak a language other than English at home, with 13.2% of all households speaking Spanish. These languages are passed from parent to child and have a powerful effect on the speaker’s life, keeping them tethered to a rich culture or tightly knit community.

And yet, such an influential force on a child’s life sometimes has no power outside of their homes. The majority of students in the U.S. attend English speaking schools. At one point in time, students were left without the option for a non-English education. In states such as California, an English-only education bill was passed, although the law in California was later recalled in 2014.

It serves to reflect the fact that, even if America has no official language, English is the dominant tongue. Most interactions out of the home – in stores, on street signs, on television – are in English. In itself, this is not a negative thing since having a universal language brings communities together. However, the predominance of English in our country has just one devastating effect: the removal of historically rich foreign languages.

The phenomenon of subtractive bilingualism

Attending U.S. schools proved to do much more than increasing a student’s English proficiency. The University of Pittsburgh finds that children in American schools “quickly lose touch with their language heritage.” This is a phenomenon dated back to 1981, noted by psychologist Wallace Lambert. In his study analyzing French-Canadian children, Lambert finds that subtractive bilingualism, the phenomenon of harming the first language by learning a second, results in “a loss of native language fluency.”

Freshman Daniela Birkmane sees this happening in her family. Birkmane and her brother spent their early years growing up in Latvia. While she attended Russian school in Latvia until her family moved to the U.S., her younger brother didn’t learn Russian. After coming to the U.S., Birkmane noticed that she was losing her ability to speak the language of her mother.

“English has always been a central part of my identity. At home, we speak Russian with my mom, but my brother and I don’t speak Russian, and even my dad sometimes doesn’t speak it. So I feel like it’s already happening [Russian is being let go],” Birkmane said. “But when I move away for college and jobs, I think there is a chance that I’m going to completely forget [Russian], which I’m trying to prevent.”

Birkmane also holds the belief that, for those who immigrate to the U.S. especially, native languages eventually become less and less prioritized.

“Over time, I definitely feel like [people, especially immigrants,] are forced to forget [their native languages], especially if they don’t join any communities or aren’t surrounded by people,” Birkmane said. “In this community, a lot of people are surrounded by people but in other places, you are just completely alone, and it doesn’t make sense to retain information you don’t need. So most of them just switch to only English.”

But beyond just the linguistic sides of a student being affected, cultural and familial ties are affected as well, highlighting how deep the roots of language truly reside.

Familial Interaction

Especially considering immigrant families living in the U.S., relationships are substantially affected, even just through the decline of native language fluency.

A study in 2011 was conducted on Chinese and Korean immigrant families with high school freshman students to see how native language loss impacted their family. Multiple findings represented the dire situation of language loss present in the status quo.

They first found a generational decline in native language fluency when comparing first-generation to second-generation adolescents. Meanwhile, the parents still had lower English fluency levels than their children. This represented the consistent language gap existent “regardless of generation or ethnic group samples, creating the potential for communication issues that may impact [the relationship between parents and children].”

While some may argue that fixing the issue of English fluency with parents is a promising solution, the results of the study prove otherwise. Considering that the results showed that parents’ English fluency may not be critical in explaining the benefits of native fluency with their children, the importance of fluency may go beyond just communication.

“It may be that adolescent native fluency improves cultural understanding between adolescents and their parents, allowing adolescents to better understand their parent’s cultural heritage and, thus, their parent’s perspective,” the study finds.

This means that communication goes beyond the borders of linguistic capabilities, implicating “social significance” as well. The study found a “direct correlation between respect for parents and native language fluency,” shown, for example, through the lack of honorifics in the English language, which are key to Chinese and Korean culture. And it’s not just in East Asian families that this familial divide occurs.

While Birkmane learned Russian when she was little, her brother did not, and this linguistic divide developed into an evident divide in her family as well. On her side, her relationship with her parents has stayed strong due to the connection she has maintained through language.

“For me, I feel like I have a much closer relationship with my family than my brother [does]. For my grandparents, they like me more because I’m able to communicate with them and express my feelings more,” Birkmane said.

Her brother, on the other hand, has faced feelings of exclusion within the family for the majority of his life.

“My brother is excluded and he doesn’t engage as much in activities,” Birkmane said. “[My relatives] treat my brother like a 5-year-old instead of a 12-year-old because the language gap is so wide.”

This has had an impact on his relationship with his family, specifically with his mom.

“He, honestly, doesn’t care about it. My mom is really upset about it — everyday, she tells me how sad she is that he’s going to forget the language, and she’s afraid that she won’t be able to communicate with her own son. But he just doesn’t care — he doesn’t want to make that attempt to learn it because he feels like he’s already been excluded for so long that there’s no point in learning it.”

But alongside a struggle in familial interaction stands a cultural decline too, affecting not only a family, but our society as a whole.

A decline in cultural ties

UNESCO phrases it well – knowing our mother tongue “fosters mutual understanding and respect for one another and helps preserve the wealth of cultural and traditional heritage that is embedded in every language around the world.”

This is notably visible in a more radical sense in the world scene right now. Ukranians, a majority of which are fluent in both Ukrainian and Russian, cling tight to their Ukrainian culture as they fight against Russia.

“More people over the last month have felt themselves to be intensely Ukrainian,” Sofi Dyak, the director of the Center for Urban History, an institute in Lviv, Ukraine, finds.

Though not agreed upon by all, Ukranians have found themselves to be rejecting the “Russian World” through methods such as sticking to the Ukrainian language. In an interview with the Washington Post, one such Ukrainian, Lidiia Kalashnykova, said that she had “no right to use any language other than Ukrainian,” continuing to say that “the Ukrainian language is actually my weapon.”

Though the emphasized ties to their native language arise from a more nationalistic point of view in the war against Russia, there is also a clear highlight of the importance of their language to their identity and culture that Ukranians associate themselves with, as do many outside the war. Birkmane sees this importance in her own heritage and family as well.

“Since I didn’t grow up in [Russia], it’s been my own connection to [the country],” Birkmane said. “And my mom tries to get us into the holidays and books. I read from a very young age — Russian books [and] Russian songs — and my brother couldn’t understand any of that. So there’s a really big cultural divide in my family where some people are excluded from the American side and some people are excluded from the Russian side.”

While it may seem like a specific phenomena, there’s a clear contrast between students who know their mother tongue and those who don’t, whether it’s linguistic or cultural.

A clear contrast and divide

Many argue that a foreign language is not a necessary skill in America, where 75% of the population speaks only English, according to a 2013 Yougov survey. Additionally, in the U.S, foreign languages are not a major requirement for a successful career or life.

Bryan Caplan from Econlib writes “We don’t learn foreign languages because foreign languages rarely helps us get good jobs, meet interesting people, or enjoy culture. Americans start in an unusually abundant and diverse economic, social, and cultural pool, so we have little reason to stray. And if Americans do decide to sample other pools, we can literally travel the world without needing to learn a word of another language.”

Though foreign languages rarely help us get good jobs, they can be of great assistance in many fields, especially in areas such as marketing, and communications. A study by the University of Florida finds that Hispanics in Florida made about $7000 more than their counterparts that speak only English.

This idea that English is the only language that needs to be spoken often translates over into acts of racism. Numerous instances have been recorded of strangers telling individuals using foreign languages to “speak English”. Similar cases have been reported at schools, places where learning and exploring should be encouraged.

For example, Carlos Cobian, a student at Socorro High School in El Paso, was told by his teacher to “speak English. We’re in America”. Another clip from NBC News shows a teacher talking about her students “right to speak American” before the students leave the class in protest.

Upon closer inspection, is there any weight to the reasoning that students must speak English due to their being in the U.S? The U.S is considered the “land of opportunity”, and the rich diversity brought by its one-million-plus immigrants annually should not be disregarded. This is the trait that sets the U.S. apart from other countries. For a country with so much ethnic variation, English should absolutely not be the only language a person communicates in. Consequently, a community of non-English speakers should not be seen as negative, but as a positive effect of such a varied population.

Additionally, history shows that English itself was an “immigrant language”, brought by British colonizers in the 17th century. If modern Americans were really speaking languages that originated from the U.S, they’d be using Native American languages such as Navajo.

Worries of Foreign Parents.

English is not only pushed on to individuals by strangers. Many parents, especially those who have a deep connection with a foreign language themselves, urge their children to speak strictly English.

There are a variety of causes for this, the main being to conform to an English-speaking society. Parents fear that their children will get bullied for a strong accent or just won’t develop English speaking skills as fast as their peers.

These worries hold a certain weight. Bilingual children are shown to develop in both languages, but at a slower rate than monolingual children.

According to cognitive psychologist Ellen Bialystok, in the case of bilinguals, “Language efficiency in children and adults tends to suffer slightly, with children learning vocabulary more slowly and adults exhibiting slower linguistics”.

Bullying is not an invalid parental fear either. A 2020 Guardian article chronicled students being bullied for their accent. Even more bizarrely, these incidents occurred in top universities.

These are undoubtedly problems that accompany bilingualism, however, the solution is not to eradicate all languages other than English. Instead, the focus should be to create more welcoming environments for bilingual people, and to encourage them to practice two languages simultaneously. We can even go as far as to advocate learning your native language, or set up more English classes for non-fluent English speakers.

Instead of telling a student to hide their accent to socially conform, we should encourage society to embrace their linguistic variation. Instead of urging kids to abandon their home languages and focus entirely on English, parents should establish a healthy balance between the two, and build communities where children can develop both tongues.

The former options are a promulgation of hate towards foreign languages, one which can develop in immigrant children themselves. The latter solutions promote love and acceptance of a diverse community. And the love, acceptance, diversity, and rich culture that accompanies our native languages is key to rooting ourselves, our family and most importantly, our heritage.

Reaching back to our roots

Though there are numerous self benefits to retaining our first language, such as improved academic performance, improved family communication and relationships and greater respect for our heritage and culture, the positives of learning our mother tongue extend beyond ourselves. A language is more than words, and our mother tongue is more than just what our parents speak. Once we come to the realization that we are the next generation passing on our family and society’s languages, it’s not difficult to see the importance of keeping that root intact.

Whether by watching the local news, foreign television, practicing with parents or requesting schools to offer more foreign languages, efforts to keep our mother tongue with us can be fruitful. Looking back when we are older, chances are that we won’t regret the decision we made to hold onto those roots that dig so deep in our familial soil. And as time goes on and our fluency and knowledge decays, our roots decay too.

As UNESCO wrote, when a language leaves the scene, “it takes with it an entire cultural and intellectual heritage.”

Birkmane couldn’t agree more. And to her, losing a language also means losing a part of her.

“It’s like your whole childhood is lost. It’s like losing a part of your identity, it’s losing those around you. It’s almost like having no community that you belong in anymore because you are never going to be fully American because you weren’t born here and you didn’t have the childhood experience of being American,” Birkmane said. “But now you no longer have the experience of this other language, and you don’t really know where you belong anymore.”