ATP: Academic Boon or Stressful Curse

ATP — the “Academic Talent Program.” You either hate it or you love it, there’s no in-between. Beginning with the Cognitive Abilities Test (CogAT) in the second grade, the selection process locates students who score in the 97th percentile to be candidates and then spend grades four through eight in the same class together. The intent is to gather like-minded individuals who strive to excel in the classroom, providing them with the opportunity to challenge themselves past the curriculum standard. However, the topic of ATP has been met with resistance, with most thinking it to be a secluded group of anti-social nerds. Even so, ATP is not the dreadful adversary many believe it to be.

One of the biggest arguments against ATP I always hear is that it disables children from learning how to form social connections. While it may seem apparent that staying with the same people for five years straight may stunt social development, ATP children are still provided the opportunity to socialize with other students. In elementary school, we still have recess and lunch, and in middle school, only English and History have designated ATP classes. They’re still allowed to go outside during breaks and lunch and are still required to take physical education classes where they can play games and socialize with other kids. Sure, there might be a few people I can think of who fit the unsocial stereotype, but there are antisocial people everywhere.

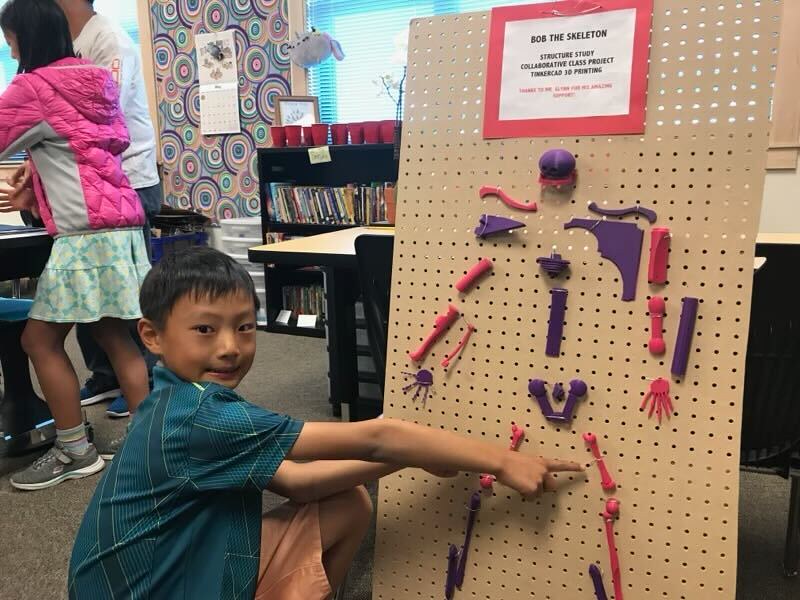

Another common critique of the ATP program is that it inflates students’ egos and burdens them with an unhealthy amount of expectations and pressure on them. While I’ll admit it is partially true, I also have to disagree to an extent. I’ve seen prideful ATP kids and I’ve seen non-prideful ATP kids; I’ve seen non-ATP kids who were full of themselves (some still are), and I’ve seen extremely modest non-ATP kids. At the end of the day, the title of being an “ATP kid” bears little significance on whether students have a superiority complex or not. Maybe it did four years ago, but do you seriously hear high schoolers bragging about having been in ATP? And that’s not to say that the experience had little impact on us. We were challenged in the classroom (honestly, eighth-grade core was a LOT of work), and had a lot of really niche opportunities like doing geopolitical simulations and learning 3D printing. This was all without an exceeding amount of academic pressure, too. Sure, there was competition (I’d actually argue that non-extreme competition is mutually beneficial for most students), but the highlight of the program was forming deep connections with peers who shared my passion for academic rigor.

I also understand that the distinction between students as being called “academically talented” and those who aren’t can feel disheartening. It’s a pretty polarizing label. That’s the one thing I would modify about the program: someone’s potential for academic success is an important factor, but it’s not everything. While I still believe it should be the main consideration for the candidates, another significant component would be a student’s passion for learning. Passion develops discipline, laying the foundations for future success both as a person and a student. So, while it’s great to be talented and smart, the program is only meaningful if students can cultivate ambition early on. As the old adage goes, “show me who your friends are and I’ll tell you who you are.”

I’d like to end by saying my positive opinion comes from the fact that I had a good ATP experience, and many of my childhood friendships were forged through the program. I’ve met some amazing people who are humble, smart, hardworking, compassionate and just the opposite of the “ATP stereotype.” And sure, they could be the exceptions. But the telling part is that ATP as a program does not shape its students to become egotistical monsters. From what I’ve seen throughout my life, those who are the very best at what they do tend to be the most humble and soft-spoken. I agree — ATP should not be an environment where children compete for the title of being the smartest, but simply being in the presence of people who inspire, challenge and encourage you, is well worth the experience.

What defines academic talent? Intelligence, of course. The ability to retain information, articulate your thoughts and recognize patterns, sure. But what distinguishes talented third graders from their peers when they’re nine years old and more interested in recess than reading?

This question is the basis of the academic talent program (ATP), which uses the CoGAT test to identify high-performing students to join classes outfitted with special learning opportunities, such as programming with Scratch and playing with Spheros. But that’s the only difference between ATP and other public school classes — one enters more history competitions and learns 3D printing in the name of academic enrichment.

The program isn’t a matter of who’s “highly gifted,” as SRVUSD claims. It’s a matter of how much time and energy has been poured into your education. It favors those with resources, defeating the meritocratic point of the whole program.

When I joined ATP in fourth grade, I stood out as the only student who didn’t take extracurricular math classes. I had been in public school for my entire education, with parents who spent the evenings reading books and playing games with me instead of making me fill out Kumon workbooks.

Some may argue that I’m the rare bad apple. But when children who don’t go to Kumon or the Russian School of Mathematics (RSM) don’t succeed in the ATP program, one begins to wonder whether it’s made for “highly gifted” children or just kids who are highly educated and subject to intense pressure. This isn’t to say that it’s a bad thing to learn advanced math or read high-level books. But it is stressful and unnecessary at such an early age, given that the push towards advanced learning doesn’t originate from children themselves but from their parents.

By the time high school rolls around, the driving force behind your education isn’t from parents, but children. Students start to take control of their futures, pursuing extracurriculars and classes based on their own interests. That’s when you leave ATP behind.

Academically, most former ATP kids agree that the program doesn’t make a long-term impact on their education. The only unique opportunities ATP provides are the higher expectations from teachers and involvement in non-curricula programs (National History Day, WordMasters and the Battle of the Books). But these programs should be accessible to all students, not just the top three percent. Then kids who were truly interested in these subjects would thrive without the sense of elitism or pretentiousness that comes with being identified as “gifted” and crammed into a room with other talented kids.

I don’t completely regret joining ATP. It was nice to have teachers advocating for and believing in me. I grew up around some of the most motivated, albeit competitive, kids I would ever meet. I met friends that I’m still close with today.

But it’s restricting to be with the same classmates for five years. While some may argue that it’s beneficial to our development to be surrounded by advanced, driven kids, the reality is that we learn to view school as a competition and to compare ourselves to each other. The SRVUSD itself states that “being in a high-rigor environment can be very challenging and some students might struggle.” Understatement of the year — especially if you’re one of the ones who don’t have the help of extracurricular academic classes to boost your confidence and performance in a hyper-competitive environment.

Don’t get me wrong — some of the ATP kids in my class are going to be attending Top 20 colleges this fall. For them, it worked exactly as intended. But “it” wasn’t the ATP program. It was the certainty that they would succeed, ingrained in them by their parents and strengthened by the heaps of advanced classes, awards and competitions. They would’ve ended up on the same path without ATP, simply by way of their parents’ and eventually their ambition.

Regardless of whether or not the program exists, there will be tiger parents enrolling their children in Kumon. But without ATP, maybe they won’t force their children to learn algebra in third grade. Let’s delay that academic pressure to middle school, or better yet, high school.

Eight years after I joined the program, as a high school senior about to graduate, I can see why parents want their kids to be selected and to show them that their future is bright. But I also see my childhood self, watching in confusion as my parents asked our neighbors what the program was about. Was it worth it? Should I join?

To my younger self and any child pondering over ATP, it’s not worth it. You’ll find your way, ATP or not. High school brings enough competition; there’s no need to start that battle in fourth grade. From one ATP alum to future students: you’re going to be okay.