Behind barbed wire: Remembering Japanese Internment in America

February 22, 2018

Takeko sits in front of the shoji doors her husband built.

Tribune reporter, Megan Tsang, sits down with her maternal grandmother, Takeko Murano Tanisawa. “Betty”, as she was known to friends, spent her formative years incarcerated with her family of 14 after the signing of Executive Order 9066 in 1942.

The cover of the yearbook.

“Follow me.”

My grandma leads me through shoji doors my grandpa built by hand and past bookshelves lined with family photo albums. She’s smiling, as she always is, and pulls out an aged book coming apart at the seams. The front cover is decorated with the words “Aquila ‘44,” beneath a picture of an eagle.

“This is my sister’s yearbook from camp,” she says. She flips through the pages, pointing out faces she recognizes and recounting memories she has.

My grandma, Takeko “Betty” Murano, was 14 years old living in Stockton on the day that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor.

“It was a Sunday,” she says, crossing her arms and looking up. She recalls the “weird looks” she got in the aftermath, but that for the most part, she never felt hostility. “My friends didn’t change at all … our school was kind of multiracial, so we had all types at that school. The teachers too.”

Not every Japanese-American at the time was as lucky. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, a flurry of anti-Japanese sentiment consumed the nation. An article in Life Magazine’s December 1941 issue included diagrams on how to “distinguish friendly Chinese from enemy alien Japs,” signs on shop fronts forbidding the entry of Japanese Americans were commonplace and the newly-coined slur “Jap” was plastered across propaganda.

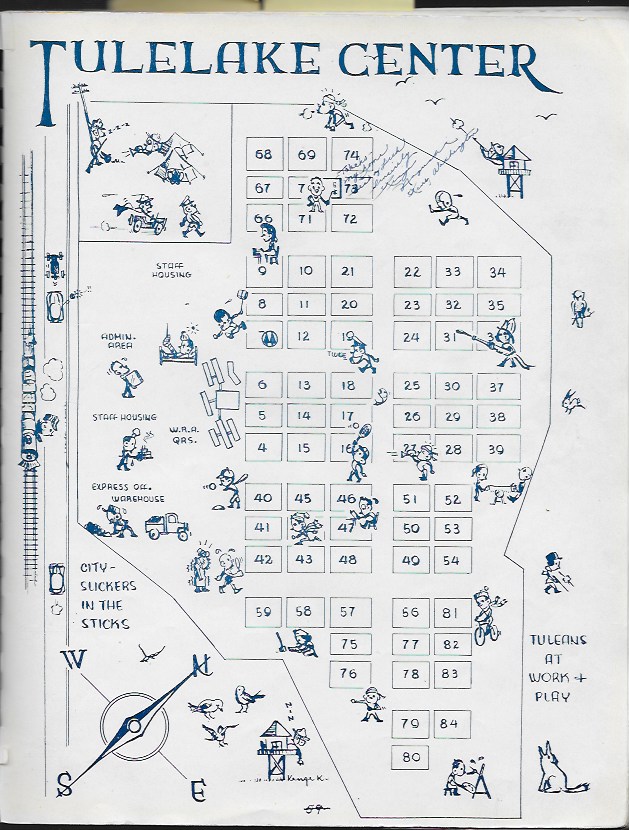

A map inside the yearbook shows the layout of the camp barracks, including sketches.

Pearl Harbor was a shaky time for America. American soil had been bombed, the Earth scorched. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech the following day was a declaration of war:

“Yesterday, December 7th, 1941 — a date which will live in infamy — the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan … With confidence in our armed forces, with the unbounding determination of our people, we will gain the inevitable triumph — so help us God.”

Two months after the military strike, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, calling for the forced internment of tens of thousands of Japanese-Americans living on the West coast.

Colonel Karl Bendetsen, the Wartime Civil Control Administrator, said, “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp,” making it clear that the question was not of innocence, but of race.

Takeko’s father was taken first.

“These big huge guys came and took dad away and said he’s declared a prisoner of war,” she says. “I guess they considered him a leader in the community, just because he belonged to so many clubs. When you have, at that time, 11 kids, then you’re active in everything.”

She remembers the uncertainty and fear that followed. Her siblings started listening to the news and rumors more carefully, relaying it all to their mother who didn’t speak English as well.

In the spring of 1942, she and her 10 other siblings — between the ages of six months and 18 — were only allowed to take what they could carry.

She describes people “dragging their luggage and looking forlorn.” Flooded with confusion and dread, she tried to console herself with her teacher’s last words to her: “It’s going to be temporary, don’t worry.”

The Stockton fairgrounds had been stripped down to become a provisional place to process internees. Ferris wheels were replaced by guard towers and horse stables were fashioned into dorms.

“I remember going to the fairs there, they had booths for games … [the fairgoers] were all happy and they all had those cotton candy,” my grandma says, recalling the atmosphere of the fair. “But now it was just empty.”

My grandmother’s family spent six more months in Stockton before she was forced to leave the only home she had ever known. They took a train to their next destination: Arizona. The internees were solemn and quiet throughout the entire ride; the only sound came from the clashing of steel as the train trudged on towards the Gila River War Relocation Center. When passing by towns and cities, they were forced to pull down the shutters.

“They didn’t want people to see us,” she explained. “It seemed like a blackout.”

The concentration camp was located on the most barren land. The merciless heat was only exacerbated by constant water shortages. Sandstorms were frequent, and whenever they heard the whistle of the breeze turn to howling and saw the dust start to swirl, they grabbed their blankets to avoid the sting of the windblown sand.

Their new home was nothing but the hollowed out shell of a room, with a sheath of tar paper resting on top of a simple, wooden frame. Showers and toilets were all communal and privacy was nonexistent. She described gaps in floorboards hastily nailed down where sand would blow in and cover the surface with grit.

“We were warned to always shake our shoes out, in case there were scorpions in them … or tarantulas,” she recalls.

As time went on, the people interned at Gila grew closer and formed a small community. There were baseball teams, a church, the occasional movie viewing and school for the children. Some internees were resourceful enough to construct furnishings out of wood scraps left over from camp construction. In the spring, tiny gardens helped to brighten the otherwise bleak Arizona landscape.

Many attempted to adapt to their new surroundings in order to preserve an ideal of quiet endurance. My grandma describes this mentality with the word “gaman,” a Japanese principle that values patience and keeping one’s struggles to themselves.

Despite the slight sense of normalcy the internees managed to create, reminders of prejudice from the outside world still remained. Like sand rising in the distance, the looming presence of armed guards caused internees to recoil.

“This is all laughable because the guards were supposed to guard us, right?” She says, raising her voice. Her usually calm exterior is visibly shaken. “No – they were guarding outside people from us because they were facing us with the guns.”

It was now 1944 Takeko was 16 years old years old. Her family had just learned that they would be transferred to the maximum security Tule Lake Relocation Camp.

In 1943, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority issued a “loyalty questionnaire” in order to recruit Japanese-American soldiers and to weed out enemies of the state. Those considered disloyal were sent to Tule Lake.

“What I was really scared of was if we would really go back to Japan because that’s [what] going to Tule usually meant,” my grandma explained.

News of the family’s relocation to the new camp was not received well by two of her older sisters. Fearing deportation, the oldest sister, Ayako, eloped and fled to Chicago. When the third oldest sister, Shizuko, graduated, she followed suit. Leaving without a word, they abandoned the rest of the family to their fate in the new camp.

At Tule Lake, my grandmother finally got to see her father again after almost two years of separation. But it was a bittersweet reunion; during the time that he was thousands of miles away from his family, he fell ill with bronchial asthma.

“When he was released to join us he had aged so much and lost so much weight people thought he was my mom’s father,” she said.

Tule Lake was located on the border between California and Oregon, caged by a ring of wildlife refuges and forests. It was colder — both in climate and mood — than Gila, and upon arrival Takeko began to feel more isolated than ever before.

“It was more desolate … And yet, people had lived there already, so it should have been more settled, ” she reflected. “It just seemed darker … It felt to me more like a prison.”

The desertion of her sisters wasn’t the only thing that fractured the family.

“Even if you were in an enclosed area, I don’t think it brought [our family] any closer, I think it did the opposite because you ate with your friends, you’re not eating with your family anymore … Mom didn’t always come to the kitchen, Dad never did and the older [siblings] worked at different places, so they didn’t eat at our cafeteria.”

Life carried on and fell into a routine — go to school, do chores, eat and sleep. In her spare time, she found work with her typing teacher, Ms. Pendleton.

Takeko is seated third from the left in the second row of this yearbook photo.

“A lot of those teachers volunteered to work in these camps, so they were teachers that really understood your condition,” she says.

The internees remained truly isolated from the outside world, so much of their news came from word of mouth.

An answer finally came when the announcement rang over the camp’s loudspeakers on that fateful day in September of 1945. It was met with both cheering and jeering. While Takeko’s family was relieved that the war was over, many others had come to feel estranged from the nation that turned against them. Of the internees who renounced their U.S. citizenship, 98 percent came from Tule Lake (Densho Encyclopedia).

Takeko’s mother, now in her forties, gave birth to Tsuruko Patricia Murano in December of that year — right around the time other families had begun to leave camp.

The typing teacher my grandmother had built a bond with sponsored her to leave early and was able to find a couple — Mr. and Mrs. Weems — back in Stockton willing to take in the now 18-year-old as a “mother’s helper”.

She lived with them for a year and a half before she graduated high school, doing chores in exchange for food and a room.

“I did a little cleaning, washed the dishes and things like that,” she explained.“But, I ate separately. I ate in the kitchen, while they ate at the dining table.”

After high school, my grandma went to business school and promptly found work as an accounting clerk in order to help support her family.

My grandma laments about a childhood lost: “When you’re young, you go to the movies and say you want to be a Sonja Henie, we want to be this, we want to be like Shirley Temple, you talk like that. But after camp, no. I just had to go out, get a job and help my parents … that was it.”

The rest of her family had experienced loss as well — the loss of the home that they had lived eight years in and their family business, the Palace Hotel on Lafayette Street.

Her parents and younger siblings drifted around, staying everywhere from a makeshift hostel set up at a local Buddhist church to an uncle’s basement.

About 40 years after the last of the camps were emptied, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, which provided reparations for the internees as well as issuing a formal apology that acknowledged the anti-Japanese sentiments that motivated internment.

Former internees still remember incarceration and the prejudice that followed them throughout their lives after camp. Even after escaping the conditions of the camp, some internees suffered long-term psychological and health issues. In a survey from “The Experience of Injustice: Health Consequences of the Japanese American Internment” by Gwendolyn M. Jensen, it was found that internees were at greater risk for cardiovascular disease and “psychological anguish” in their lives after internment.

The poignant effects of this event sometimes transcend generational boundaries, with studies revealing a divide between the “nisei” — the second generation of immigrants, like Take, that made up the majority of internees — and their children, the “sansei.” In an essay on Japanese internment, Nobu Miyoshi describes the effects of the survivors’ avoidance of discussing their experiences with their children.

“In many respects the Nisei have been permanently altered in their attitudes, both positively and negatively, in regard to their identification with the values of their bicultural heritage; or they remain confused or even injured by the traumatic experience,” reads an excerpt from Miyoshi’s “Identity Crisis of the Sansei and the Concentration Camp”.

The end of war did not mark the end of racism, and many internees felt pressure to assimilate in order to escape race-based hostility. Various memorials and museums try to preserve their fading Japanese culture and remember Japanese internment. Another reminder is the Day of Remembrance, observed on Feb. 19. Taking place on the same date as the signing of Executive Order 9066 in 1942, the event memorializes the internment of the 120,000 Japanese Americans who were incarcerated on the West coast from 1942 to 1946.

As I’m walking out of the front door of her house, my grandmother calls me back and hands me a flyer.

“It’s for the Day of Remembrance. It’s this whole to-do in San Francisco. You should go.”

After taking the flyer, I suggest that we attend the event together. My grandmother laughs as she waves goodbye.

“Oh, I don’t need to go. I already remember.”